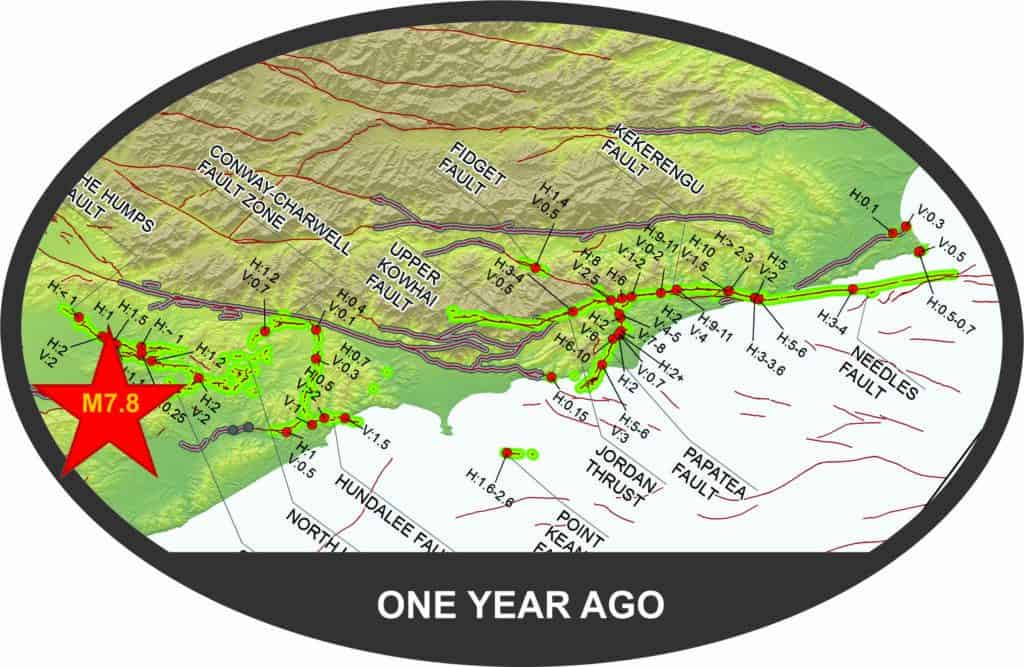

First, we remember the dead. The two Kaikōura earthquake victims weren’t killed by the earthquake so much as by failure of the buildings they were in. But a year on from the magnitude 7.8 earthquake that shook central New Zealand, is also a time to be thankful. Thankful that most of us who experienced the earthquake survived it, thankful that the earthquake didn’t happen under a city this time, thankful that it happened at night so no-one was buried under the numerous landslides on State Highway 1, thankful that the tsunami impact was lessened by low tide and a freshly uplifted coastline.

The first anniversary of the Kaikōura earthquake of November 14 2016 is obviously a time for assessing recovery. There is solid progress – everyone has food, water, power; the whales are back; the railway is open for limited services. But many do not have safe homes or even offices. State Highway 1 north of Kaikōura is closed and other parts of the highway network are fragile. Wellington’s port is only partially functional. Buildings are still being demolished. There are very many deeply tired and stressed people – on the land, in schools, businesses, government departments – all attempting to cope with upheaval and establish a sustainable “new normal” in the post-earthquake environment.

This was a massive event for a small country to deal with. As we know from the Christchurch experience, recovery is a long process. So, we are now in a double-whammy of earthquake recovery, for, although we’ve marked the sixth anniversary of the 2011 Christchurch earthquake, we have not fully recovered from that devastating event.

The surest way we can speed up recovery after future events is to build resilience – the ability to readily recover from shock. The word “resilient”, originally applied to people, is now applied to everything from pipelines that don’t break, or can be repaired quickly, to communities who support each other through a crisis. A little action on resilience planning and spending now results in less money spent in disaster recovery and, more importantly, happier humans. This is an important benefit of marking earthquake anniversaries – remembering how people were impacted and keeping resilience on national and personal agendas.

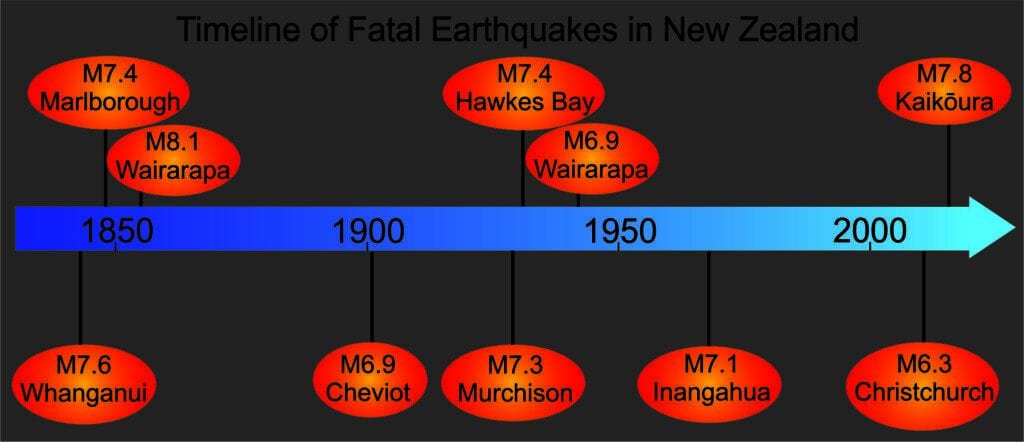

Measuring how far we’ve come as a nation in living wisely with earthquakes is a good reason to mark longer anniversaries of historical earthquakes. The sesquicentennial for the 1855 AD Wairarapa earthquake shone an interesting light on progress since European settlement of Wellington. Some strides have been huge – yes, we now know we live on a plate boundary, we’ve invented base isolators, and we have the Earthquake Commission. But can’t we hear the voices of those early Wellingtonians – those who witnessed the 1855 tsunami washing into Lambton Quay and who trembled in their tents for months after the earthquake – asking us so many questions? “Why did you keep building in unreinforced masonry? Why have you been building on low-lying land so close to the sea, and reclaiming land without strengthening it? Why have you been building on really steep hillsides?”

The problem is big gaps between big earthquakes. Earthquakes go off the agenda. We forget. That’s why I’m in favour of marking their anniversaries.

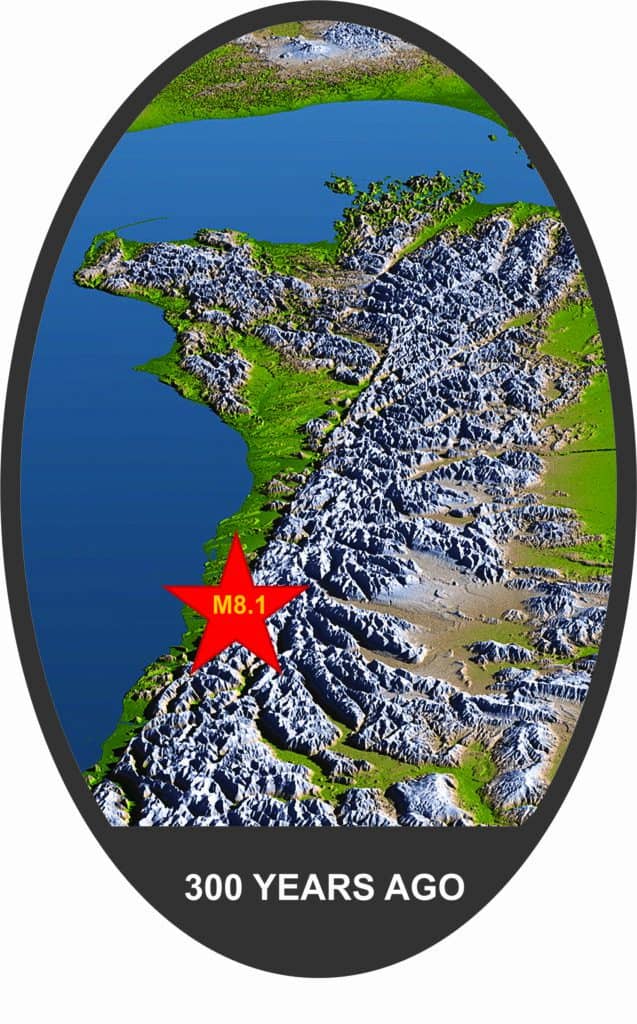

Marking a three-hundred-year anniversary – a tricentenary – may seem ridiculous for an earthquake. Nevertheless, that’s exactly what earthquake geologists are doing at a conference in Blenheim in mid-November. Why recognise such ancient events? At an aspirational level it’s about striving to be more useful to society – collecting what we have learnt, highlighting what we don’t know, and asking, “What are the next most important questions we can answer?”

This year marks the tricentenary for the last major event on the Alpine Fault. In 1717 the earth’s crust ripped apart in a magnitude 8.1 earthquake. Mountain-sides fell towards the sea, rivers were blocked, forests damaged throughout the West Coast of the South Island. We were not around to witness. But there are trees that still bear the scars. And rocks and landscape have been interrogated to give us what we know of this epic earthquake.

The 1717 earthquake paints a picture of what the next Alpine Fault earthquake may look like – but now, when we add the people, buildings, transport systems, and water supply, the scenario gets much messier. The significance of the Alpine Fault tricentenary expands like a balloon when we consider how often these major earthquakes occur – on average every 300 years. When was the last one? Three hundred years ago.

The 300-year repeating pattern is known from recently-discovered evidence of 27 past earthquakes preserved like fossils next to the fault in Southland. We use 8,000 years of past earthquakes to peek into the future and see that the next one is inevitable. These earthquakes recur remarkably regularly in time but there is enough variability that we can’t pinpoint the year, or even the decade, when the next one will happen. We can estimate that there’s a 30% chance of the next big one happening within 50 years. We can’t predict earthquakes but this is one of the highest quality datasets worldwide for forecasting their likelihood – certainly enough to motivate action on building resilience.

Many people are hard at work. Individuals are beefing up their camping gear. Businesses are installing generators and arranging back-up communication systems. Hospitals are securing vital equipment. Marae are gearing up to be emergency centres. Organisations that provide life-lines (water, electricity, communications, transport) are making networks more resilient. Civil defence groups are planning how to best coordinate after such an event. Local government are looking hard at their land-use plans and considering moving whole towns. Ministries are reviewing policies and codes. And, hopefully, the new government will encourage more of this work across more of the country.

But you don’t have to spend much time or money to make your post-event life more comfortable. Time-travel briefly to the days, weeks, months after the next major earthquake / eruption / flood / tsunami / landslide and ask yourself what you’re regretting most.

“I wish I’d asked mum to collect the children on days when I’m out of town.”

“If only I’d stored more water, I wouldn’t have to walk and queue for so long.”

“It would have been good to have a bit more food so I could help the neighbours.”

“It’s my fault I didn’t secure that bookshelf…”

New Zealand is a stunning place to live. There’s no way we are walking away from it. We just need to keep learning how to live with our natural hazards wisely – in part by remembering the frightening events.

However, as George Bernard Shaw said, “We are made wise not by the recollection of our past, but by the responsibility for our future”. Yes, let’s mark the anniversaries of earthquakes. Let’s remember them in vivid detail. And let’s use that memory to improve resilience – each of us in small ways – for a better future.